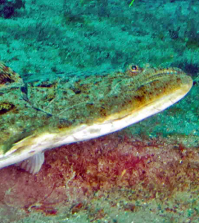

How Deep for Halibut?

Jim Reed found this hefty halibut on a 130-foot hump on the

northern Washington coast. (Terry Rudnick photo)

“How deep do I have to fish?” It’s one of the most frequently asked questions from anglers just getting into the halibut-fishing game.

The first answer that comes to mind is, “As deep as necessary.” That’s not what they want to hear, but it’s as good a starting point as any when talking about searching the varied contours of the ocean floor for the Northwest’s trophy bottomfish, the Pacific halibut.

Many people associate halibut, especially larger halibut, with fishing the vast depths of the Pacific and its major inland waterways, using pool-cue rods, reels the size of small dogs and sinkers weighing several pounds. Yes, there are places and situations where such “extreme” fishing measures are required, but, depending on where in the halibut’s range you happen to be fishing, you may just catch an eating-size—or even trophy-size—halibut in 50 feet of water.

Put simply, it isn’t the water depth per se that determines where you might find halibut, but the bottom topography and what it provides in the way of suiting a halibut’s needs. You might find that stretch of happy halibut grounds at 75 feet, 750 feet, or anywhere in-between.

First, let’s dispel the myth that we’re looking for a good “halibut hole.” Pacific halibut don’t tend to live at the bottom of deep holes or dips in the ocean floor. In fact, pretty much the opposite is true. You’re much better off looking for “halibut humps,” the reefs, seamounts, ledges and rock piles that make up the underwater hills and mountains of the marine world. These are the places where bait fish, crustaceans and other forms of halibut food congregate and flourish, where upwelling, tides and currents wash them back and forth across the bottom contours, and where hungry halibut can hide away and wait for an unsuspecting meal to pass by within striking range.

Yes, as it happens, down here in Washington, Oregon and the rest of the halibut’s southern range, many of those underwater hills and mountains that make for good halibut habitat are located in deeper parts of the ocean, sometimes well offshore. Oregon’s Heceta Bank, for example, is a sea mount that rises up from the depths of the Pacific to a “shallow” 700 feet or so, the same depth range that Westport anglers fish when they chase halibut around the drop-offs of Grays Canyon or where the folks out of LaPush fish near the southwest corner of the halibut and bottomfish closure area. It’s still deep-water fishing, but you’re working ledges and slopes that drop off into much deeper water that surrounds them.

But terms like “deep” and “shallow” are relative, and when you move closer to the beach, into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, or especially if you work your way up the coast of British Columbia and Southeast Alaska, you find that the hills and humps sometimes rise up to within only a few fathoms of the surface, and the “deep” water surrounding them isn’t all that deep, either. Water depth atop Coyote Bank, in the middle of the Strait north of Port Angeles, for example, is only about 100 feet, and if you make a southwesterly drift along the U.S./Canada border from the top of the hump, you eventually drop off into about 250 feet of water. The numbers are somewhat similar for Hein Bank, where you may start out in 125 feet of water and, depending on how far and what direction you drift, you may soon find yourself at depths of 300 to 400 feet. One of my favorite sections of underwater hillside off Dungeness is about 130 feet deep at the top and about 350 feet deep at the bottom, although I usually start reeling ‘em up at about 250 because I’m getting lazier in my old age.

Every underwater hillside that has halibut potential is a little different from all the rest, and there’s no magic formula for determining the perfect places to try. Some halibut humps rise up several acres in size, others no wider than your living room. The very important difference between all those humps, hills and mountains down there is the kind of material they’re comprised of. Some may be solid rock, others primarily cobble, others smaller gravel, and some may even be sand and gravel. If there’s plenty of food around, the composition of the bottom really doesn’t matter all that much to a halibut, but as a general rule, some kinds of bottom tend to provide more of what a halibut likes than others. The makeup of the bottom may also be an important factor in how effectively you can fish that spot.

The bottom composition that seems most attractive to halibut is cobble or cobble and gravel, and the hillsides where those materials predominate tend to be fairly gradual, without a lot of steep drops or quick changes in depth. That kind of bottom structure is relatively easy to fish, because you can keep your gear bouncing effectively along the bottom without the constant threat of hanging up, losing tackle and wasting important fishing time re-rigging. Rock piles and other solid-rock structure, on the other hand, tend to feature more severe drops and jagged surfaces, making it difficult to keep your bait or lure near bottom without constantly snagging up and losing tackle. If your chart or depthsounder indicates a steep drop in bottom depth, it’s almost always telling you that the bottom is a rocky one. And fishing at any particular depth range doesn’t determine what kind of bottom you’re likely to encounter; you’ll find both solid rock and gravel/cobble bottoms in areas as deep or as shallow as you may want to fish.

The author was able to reach this shallow-water chicken halibut with a small pipe jig fished on relatively light tackle. (Harley Graves photo)

Whether the slope you’re fishing is 400 feet high and several hundred yards long or 20 feet high and 50 feet long, you may find halibut at any point and any depth along the way. The standard strategy is to begin fishing near the top of the hill and drift down-slope with the wind and/or the tide, paying out line to keep your rig near the bottom as the depth increases. Halibut often lie in wait with their noses into the current, watching for smaller fish, crustaceans and other tasty tidbits that may wash by. Small humps, steps or breaks in an otherwise constant slope may be especially attractive ambush points, as are the downhill sides of “shoulders” where the bottom slope flattens out for a short distance before continuing its decline.

Although the same baits and lures that fool halibut in shallow water are equally effective in deep water, you’ll need to up-size jig and sinker weights and beef up the rest of your equipment to handle those terminal rigs needed for deeper water. If you’re going to fish those 500- to 700-foot depths offshore, you’ll need a stout rod in the six- to seven-foot range with a long butt and a roller tip. A high-capacity reel, preferably a two-speed, should be loaded with braided line in the 80- or 100-pound range. Without such equipment, you simply won’t be able to fish the three- or four-pound leadheads, pipe jigs or cannonball sinkers you’ll need to reach bottom.

You can use that heavy gear in shallow water if you want, but it’s likely to wear you out pretty fast and take some of the fun out of the experience. You might want to go with a rod that will handle 16- to 32-ounce weights and a reel that will hold 200 to 300 yards of 50- to 80-pound braid.