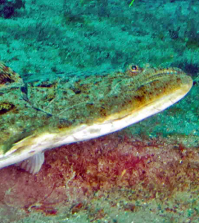

How to Boat a Halibut

Another halibut season is upon us, and it’s a safe bet that dozens-perhaps hundreds-of hefty flatties will be lost at the boat during the next few months by anglers who weren’t as prepared for halibut-fishing success as they thought they were. The Pacific halibut may not be the smartest fish in the sea, but it’s one of the strongest and toughest in this part of the country, and if you don’t have a battle plan for landing one or the equipment to carry out that plan, this fish may just beat you up and leave you wondering who really is the stupid one.

Let’s face it, anglers down here in Washington, Oregon and northern California may not get all that many chances to hook a halibut during the course of our relatively short seasons, so when it happens, why blow it? If you go to the trouble to put yourself in the right place at the right time, with the right bait or lure, to hook one of these sweet-eating trophies, you damn well better be ready to show it who’s boss when you get it to the surface or all your previous efforts will be for naught. The bigger the halibut, the more important it is to be prepared, but even a little 15-pounder can kick your butt if you don’t know what to do when you get it to the side of the boat.

One of the best things you can do to put most of the halibut you hook into the boat is to choose your fishing buddies wisely and never go halibut fishing without them. Murphy’s Law dictates that the one time you go fishing alone will be the day that you hook the biggest, meanest halibut you’ve ever encountered, and you won’t have a chance, so don’t ever fish alone. Unless you’re a really experienced halibut fisherman-or really lucky-the odds are against you when you’re going one-on-one with a 40- or 50-pound hali that’s in a foul mood because it’s choking on a leadhead jig and being yarded from its comfortable home in the depths up into the glaring light of day. You want to have at least one other person in your corner under those conditions.

Everyone in the boat needs to remember that, once a halibut is hooked, they’re a team, and they all need to be on the same wavelength. When one guy hooks a fish, the others reel in as quickly as possible and get ready to carry out whatever their role might be in the events that are about to unfold. People who insist on continuing to fish while you play your halibut could well cost you your fish, either by tangling their lines with yours or by not being ready to help out when their help is needed. Lots of things can go wrong as a halibut comes to the surface, even if everyone’s doing what they should, so you really don’t need some selfish jackass in the boat who’s going to add to the potential problems.

The best method of getting a halibut in the boat depends on a number of variables, including the size and strength of the fish, size and strength of the boat, size and strength of the people aboard the boat, size and strength of the tackle being used, available halibut-landing equipment, where and how well the fish is hooked and the crew’s experience at landing halibut.

Of all these variables, the only two that are really beyond your control are the size and toughness of the fish at the end of your line and how well it’s hooked when it gets to the surface, and the fact that they’re beyond your control makes them the most important in determining how you go about trying to land the fish. That is to say, you have more options when it comes to latching onto and controlling a smaller halibut, and there’s a lot less urgency in how and how quickly you do it if it’s obvious that the fish is well-hooked on tackle that’s up to the challenge.

So let’s start with the little guys. Chicken-size halibut of, say, 20 pounds and under can be scooped out of the water in most situations with a decent-size salmon net. As with salmon, lead them into the net head-first and close the bag around them quickly by pointing the net handle toward the sky. You have to be especially careful with a net if you’re using a spreader bar or teaser hook above your main rig, because either of these may become entangled in the mesh before the halibut is fully in the net, and that, of course, can result in a lost fish. The only other potential problem with netting a halibut is that a flopping, twisting halibut and its sharp teeth may become so entangled in the net’s mesh that it takes five minutes to remove the fish from the net once it’s landed. Oh yes, and a halibut will also slime-up your net pretty good, so be sure to rinse it thoroughly as soon as you’re done landing your fish.

A gaff is my weapon of choice for “mid-size” halibut of 20 to 50 pounds, and thousands of other Northwest halibut anglers seem to share that preference. Choose your gaff wisely, though, and learn how to use it right or you’ll lose a lot more halibut than you should with this highly effective piece of equipment.

The first thing you need to know about halibut gaffs is that the category DOES NOT include hay hooks and those little straight-point models with the 18-inch wooden handles. Both are designed to be wielded with only one hand, and there’s really no way to grip them effectively with both hands, which means that if you are lucky (or unlucky) enough to stick the point into a 40- or 50-pound flattie, you can’t control it when it starts to thrash and twist, let alone lift it into the boat if and when the thrashing and twisting subsides. And should you stick one of these undersize gaffs into a larger fish, there’s almost no chance the outcome is going to be what you want it to be. Lots of halibut are mortally wounded and lost by anglers using gaffs that are too small, and relatively few are successfully boated.

You need a gaff with a handle of at least three feet to accommodate two-hand use, and I prefer the traditional “hook” type gaff over the straight-point models by a wide margin. Halibut have a tendency to twist off the straight points, but if you keep some lift with the hook-style gaff they tend to stay stuck. My halibut gaff is an Aftco Taper-tip aluminum model with a four-foot handle and three-inch hook throat (gap), and it’s as strong and dependable now as it was when I got it more than 20 years ago. I won’t hesitate to use it on halibut up to 60 pounds, and it has put dozens (maybe hundreds) of good fish in the boat without ever failing me, even though a few times I’ve hurried my “shot” and didn’t stick the point exactly where I should have.

Which brings us to the how-to part of gaffing a halibut. The most important thing to remember is that you don’t just haul off and start swinging the gaff at your fish. That may be the best way to knock one off the line but it’s not the best way to put fresh halibut in the fish box. I like to lay the hook across the fish’s back and sink the point home with a quick upward pull. Some people let the fish do its thing for a few seconds before bringing it aboard or trying to subdue it over the water, but my approach is to get it headed into the boat as soon as I sink the gaff. With smaller fish the sticking and the boating can be done in one motion, but the bigger ones may require a second effort. My philosophy is that the longer a halibut is in the water, the more opportunity it has to twist or tear off the gaff and disappear.

Unlike some halibut anglers, I don’t gaff a halibut in the head. If you go for a head shot and miss, you might knock a fish off the hook or break the line. What’s more, a halibut can use the full length of its body for leverage when it’s gaffed too close to one end or the other, so you eliminate some of its strength when you gaff it closer to the center of its body. I try to sink the point a few inches behind the back of the gill cover, something like one-third of the way back from the tip of the nose. I shoot for the back side, not the belly side, because there’s a lot more flesh to hold the gaff. Sure, you put a small slice through prime fillet, but that’s much better than hooking into the thin belly wall and watching your halibut twist and tear off the gaff half-way between the water and the gunwale.

Some people use a flying gaff for halibut, but if I’m going to have a good-size fish at the end of a tether, I’d rather have a harpoon head at the end of that tether than a gaff hook. If you allow the rope to go slack with a flying gaff, a halibut could shake the hook, but there’s no chance of that with a harpoon line running through its body.

Harpooning is the preferred landing method for larger halibut, because it lets you get a line on the fish without having to try to gain immediate control and slug it out nose-to-nose with a ticked-off fish that may be as big as your are! A properly rigged harpoon will quickly do the job of tiring a halibut without much danger of bodily harm to the angler and crew.

As with gaffing, I don’t like to harpoon a halibut in the head for fear of hitting the line or jarring the hook loose. I go for the body, preferably a few inches behind the head, and I try to come close to the halibut’s lateral line without hitting it. If you nail the lateral line straight-on you’re also going to hit the spine, and with a large fish that spine is thick enough to prevent the harpoon head from going all the way through the body. That’s bad, because you need the head to go all the way through the fish so that it toggles open and doesn’t pull back out through the entry hole. If you’re going to harpoon a halibut, rear back and do it with authority to be sure the point goes completely through, or risk killing and losing a trophy fish.

Whether your harpoon head is the long, thin type made of stainless steel or the traditional spearhead type made of brass, it will have a short length of stainless braded wire attached to it, and you should have at least 12 feet of three-eighths to half-inch nylon line tied to the end of the wire. Some people tie or braid a loop into the end of the line and either hang on to it after harpooning a halibut or tie it off to a boat cleat, but I recommend against both of those strategies. Being at one end of a rope with a big, angry halibut at the other end can get you hurt, wet or both, and if you tie off to the boat there’s no give when a surging fish reaches the end of the tether. Lines break, cleats get pulled out, and fish break loose to die slowly, so I advise against that approach.

Instead, tie a large, inflatable buoy to the end of your harpoon line and let the fish run with it after you plunge the harpoon home. The buoy may disappear for a few seconds, but towing it around will quickly tire the fish, and you can then use the harpoon line to retrieve it and start getting it under control. I use the size A-2 (15.5-inch diameter) Polyform buoy for this kind of work, but if you’re targeting big fish, especially in Alaska, you might go up a size to the A-3 (18.5-inch diameter).

Once they have control of a halibut with the harpoon line, many anglers will cut or tear a gill arch or make a cut in the soft tissue behind the gill cover to bleed out their halibut while it’s still in the water. You should, of course, bleed any halibut you’re going to keep, and doing it while the fish is still in the water makes for a much cleaner boat and begins sapping the fish’s strength before you have to deal with it on deck.

Shooting is an option if you want to dispatch a really large halibut before you bring it into the boat, but you want to be sure to make your shot count. A halibut’s brain is located just behind the dorsal-side (left) eye, and that’s where you want to place the shot. If you hit close to the brain you’ll probably stun the fish, which might be enough, but if you hit the brain most halibut will die instantly. Be ready to get a gaff into your fish or get a line around its tail immediately, because it’s likely to sink soon after being shot.

If you net, gaff or harpoon a halibut and bring it onboard while it’s still strong and lively, as I usually do, it’s essential that you get control of it immediately. I like to keep a gaffed halibut on the hook while one of my fishing partners gives it a hickory shampoo with one solid rap behind the eyes. I want to stun it but not kill it, because the next step is make a deep cut into the tissue right behind a gill cover to get it bleeding. If the fish is cooperating we make a second cut just above the tail, all the way through the spine, to both immobilize it somewhat and help it bleed out even more thoroughly. Smaller halibut will then go into the fish box to bleed out and die, but larger ones will be tied into the “U” position (head and tail tied together so that the body forms a U shape) and lashed to a cleat for as long as an hour before they go into the box. If I haven’t already made the tail cut, I’ll do that after the fish is U’d up. The job of getting a halibut in the U position, by the way, is easiest if you use a meat hook or very large fish hook tied to about six feet of quarter-inch or three-eighths-inch cord. Just stick the hook into a corner of its mouth, throw a loop around the tail and draw both ends up as close together as you can get them before making a couple more tail wraps and tying off the cord.

Remember to keep your halibut as cool as possible, especially those fish you catch early in the day. I like to keep a few blocks of ice in my fish box, especially when the weather is warm, but early in the year you can get by just fine by keeping them in the shade and/or covering them with damp burlap. Avoid dragging halibut around in the water, because surface temperatures alongside your hull are much warmer than you think, and you may have spoiled fillets by the time your fishing day is over.