Finding and Fishing Halibut Humps

One of the more common misconceptions among Northwest saltwater anglers is that there’s little more to halibut fishing than tying something big onto the end of your line, lowering it to the bottom out there in the middle of nowhere, and waiting for a fish half the size of your boat to commit suicide. It happens that way now and then, but I wouldn’t depend on that halibut-fishing strategy any more than I’d count on winning two or three million in the lottery.

On the other hand, it isn’t rocket science, either. Remember one key rule and you’ll catch your share of these prized bottomfish. Successful halibut fishing is just like buying real estate; the three most important considerations are location, location, location! The biggest key to catching fish consistently is finding the places that hold halibut, then fishing those spots the right way. If they were honest about it, serious and successful halibut fishermen all would tell you that big, sharp hooks, heavy jigs, braided line and well-made harpoons aren’t as important as their electronics-depthsounders and GPS units-when it comes to putting halibut in the fish box.

On the other hand, it isn’t rocket science, either. Remember one key rule and you’ll catch your share of these prized bottomfish. Successful halibut fishing is just like buying real estate; the three most important considerations are location, location, location! The biggest key to catching fish consistently is finding the places that hold halibut, then fishing those spots the right way. If they were honest about it, serious and successful halibut fishermen all would tell you that big, sharp hooks, heavy jigs, braided line and well-made harpoons aren’t as important as their electronics-depthsounders and GPS units-when it comes to putting halibut in the fish box.

Although some anglers talk about halibut “holes,” you wont find many flatties at the bottom of deep basins. Likewise, neither vast sand/mud flats nor rocky pinnacles-polar opposites when it comes to bottom structure-are particularly productive places for halibut anglers to spend their time.

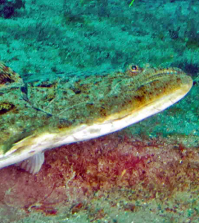

Halibut are primarily ambush feeders, lying in wait and pouncing on smaller fish, crustaceans and other tidbits when they swim or drift within striking range. The best ambush sites are places where halibut can hug the lower edge of a structure break, hiding behind that little ledge or subtle drop-off where they can’t be seen by prey species until they pass over the break, when it’s too late. Especially productive are places around the edges of underwater plateaus or along breaklines where a gently dropping bottom takes a more precipitous drop.

Potentially productive contour breaks can be found on a small scale in thousands of places throughout the marine waterways of the Pacific Northwest, but a “halibut hump” the size of a room or even the size of house is virtually impossible to find day in and day out, and doesn’t have much potential for holding a large number of halibut. Anglers find most of these small, isolated fishing spots by accident, not design, and hardly ever find them a second time.

To find consistent halibut fishing day-in and day-out, you’re better off fishing the bigger, more obvious humps. They’re much easier to find, usually easier to fish, and are likely to hold larger populations of baitfish and, therefore, larger numbers of halibut.

Some of the best-known halibut humps here in Washington are found between the west entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca near Neah Bay and the east end of the Strait at Whidbey Island. A partial list would include (west to east):

-The subtle breaklines off Koitlah Point, better known as the Garbage Dump, just west of Neah Bay.

-The series of structure breaks off the mouths of the Sekiu and Hoko rivers, west of Sekiu.

-The gently sloping flats and breaklines off the mouth of the Twin Rivers, east of Pillar Point.

-The long structure breaks paralleling the coastline from the mouth of Whiskey Creek to Tongue Point, about a dozen miles west of Port Angeles.

-The “Humps,” a series of fairly sharp drop-offs just northwest of Port Angeles.

-Coyote Bank, an underwater plateau that spans the US/Canada border northeast of Port Angeles.

-Hein Bank, the large underwater plateau about eight miles north-northeast of the Dungeness Light.

-Eastern Bank, another large plateau about four miles southeast of Hein Bank.

-Dungeness Bank, a good-sized plateau off the tip of Dungeness Spit, near Sequim.

-Dallas Bank/Protection Island, near the entrance to Discovery Bay.

-Smith Island and Partridge Bank, at the north and south ends of a vast series of flats and drop-offs with miles of potential halibut-holding water.

All of these well-known halibut humps, along with many smaller, more subtle fishing spots, are detailed on NOAA charts, so they’re easy enough to locate. The key is to prospect around a little with your depthsounder to find the actual slopes and structure breaks that hold fish and figure out how to best present your bait or lure so that it’s most likely to pass within range of a willing customer.

Fish these slopes and breaks “downhill” as much as possible, working your way from shallow water to deeper water. The downhill drift is more effective for two reasons: halibut are watching for food to come at them in that direction, and you’re not as apt to hang up and lose tackle as you would if you were drifting from deep to shallow water.

On many of the banks in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, achieving a downhill drift generally means fishing from east to west on an ebb tide and west to east on a flood, but that rule doesn’t apply everywhere. You may have to consult the current tables, adjust to wind direction and just plain experiment to get that downhill drift you’re looking for. Start at or near the top of a drop or plateau and work your way down the slope to whatever depth you and your tackle can accommodate.

When tides and currents allow, work your way lengthwise along break, dropping over the edge as often as possible as you work your way along. Staying on the edge for long periods is sometimes difficult, but it can pay off because you spend more time with your bait or lure in the zone where hungry halibut are lying in wait.

While fishing for species like lingcod may be best on a slack tide when you can fish straight up and down and have less chance of hanging on the bottom, halibut fishing is best when the water is moving, because that’s when bait is more active and halibut are more likely to be in their ambush/feeding mode. The water movement also keeps you moving along, covering new territory as you drift with the tide. Many of my favorite halibut humps fish a little better on an ebb tide, but the flood can be productive, too, so don’t limit yourself to just one tide a day.

Gravel, cobble and small rock, often with some sand, comprise the bottom of most slopes and drop-offs where halibut congregate. Fishing is easier over this type of bottom than it is on the jagged pinnacles and rock piles where you’ll find lingcod and rockfish, making it a little easier (and less expensive) to get away with “walking” a sinker or jig along the bottom.

But just because the bottom is a little more forgiving, don’t assume that the best technique is to park your rod in a holder and drag your gear along the bottom for hundreds of yards at a crack. It’s better to use the lift-and drop approach, banging bottom regularly to help draw fish in for a closer look, then raising your offering several feet into the water column to make it visible at a greater distance. Be sure to pay out line as needed to stay near bottom as you work your way down the slope into deeper water.

There’s no magic depth for halibut fishing; it’s the drop-off that counts, so don’t get hung up on trying to fish at 200 feet, 300 feet or some other depth where you or someone you heard about caught a fish last week or last year. You’re likely to be fishing a slope that eventually drops off into much deeper water, but that’s all relative. That slope may drop from 50 feet to 300 feet or it may drop from 450 feet to 700 feet. The main thing is that somewhere along the slope there are breaks where the bottom drops off a little faster and forms an edge where halibut can ambush a quick meal.