Halibut Anglers: Drift or Anchor?

Like all fishermen, halibut anglers have to make a few major decisions every time they hit the water, decisions that will ultimately determine whether the day is a successful one or just another day. Get all the where’s, when’s and what’s right and you’re a hero; make even one little miscalculation and you come home fishless. One option that more and more Northwest halibut anglers are trying to decide on these days is whether they should anchor or drift. Only a few years ago, everyone around here drifted, but anchoring has long been popular in some of Alaska’s well-known halibut fishing spots, and in recent years the technique has started catching on here in the Pacific Northwest.

Even though I caught my two largest halibut ever while anchored (in Alaska waters), I’ve caught the vast majority of my fish drifting, because that’s the way I fish about 99 percent of the time. Anchoring, though, certainly has it advocates, so let’s take a closer look at both techniques, and you can decide for yourself.

Put simply, drifting takes you to the fish, anchoring requires that the fish come to you. But there are things the anchored fisherman can do to improve the chances of fish coming his way. Down here near the south end of the Pacific halibut’s range, where the halibut managers say we’re fishing on only about two percent of the total population, just sitting and waiting for one to happen by could lead to a lot of long, fishless days. Halibut simply aren’t that abundant, even in some of the better-known inshore fishing spots.

So, what can the anchored-up halibut angler do to increase the odds of a hungry ‘but finding his bait? He does something to draw ‘em in and get ‘em swimming his way, something like chumming. Like many other species of sport fish, halibut depend on their olfactory organs (noses) to locate a lot of the stuff that goes into their mouths, so using chum to create a scent trail can be an effective way to draw fish into the range of your hooks. Not only that, but all that sweet-smelling stuff in the water may actually stimulate halibut to go on the bite and actively seek out food.

We’re not talking about the chumming technique you might use for kokanee on a 40-foot-deep lake, because the fish you’re trying to attract may be down there 300 feet or more, but there are certainly ways to effectively use chum when you’re fishing halibut off the anchor. First, you have to get the chum down there, and many anglers accomplish that by stuffing a mesh bag or basket with various goodies and attaching the chum bag to their anchor or anchor line. That way, the source of the scent is up-current from the boat, so halibut following the scent trail have to pass by the baited hooks as they move toward the chum bag.

There are, however, a couple of drawbacks to the chum-bag-on-the-anchor system. One is that conditions out on the halibut grounds often dictate lots of scope (the length of line between the boat and the anchor), so you may be fishing several hundred feet down-current from your chum bag. Scent dissipates rather quickly down there, so the positive effects of chumming may be minimal at best if you’re fishing that far below it. And, because chum leaches out and loses its punch pretty fast, the chum bag needs re-filling at least every hour, which is a major project no matter how you cut it when the bag is attached to an anchor at the end of 500 feet of anchor line.

Some anglers use their downriggers as a delivery system for their chum, which certainly makes it easier to keep the chum bag full of fresh goodies. If you go that route, just remember to hit the up button on the ‘rigger as soon as you hook up on a fish. Speaking from experience, giving a halibut an opportunity to tangle you in the downrigger wire rarely results in a pleasant outcome.

What do you put in that chum bag or chum basket? Some anglers go with whatever they’ve got lying around, others have their special secret concoctions. Herring, anchovies, sardines, squid, octopus, shrimp and clams are among the favorite ingredients. Some anglers grind them, some dice them, some smash them and some leave ’em whole, depending on which bait or combination of baits they’re using. In addition to natural baits, commercial and home-brewed scents often find their way into the chum bags of Northwest halibut anglers.

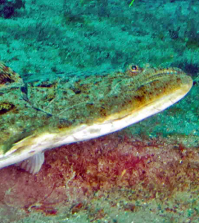

Whether or not you use chum, choosing the right places to anchor is key to halibut-fishing success. Obviously, you want to drop the hook in places where halibut are likely to hang out, or at least pass through from time to time, so avoid large expanses of flat, open bottom where there are few topographical features to hold baitfish or provide potential halibut ambush points. Jagged, rocky bottoms may hold a halibut or two, but you’re more likely to be pestered by rockfish, lingcod, cabezon and other species. You’re also likely to spend a lot of time hung up on the bottom instead of fishing effectively, not to mention the fact that anchoring on those grabby bottoms can get both dangerous and expensive! Much better possibilities include the upper edges of underwater humps and ridgelines, stair-step drop-offs, current breaks and other underwater structure where bait is likely to congregate and where halibut can lie in wait on the down-hill side of a ledge or shelf and watch for various forms of protein to drift by.

Just because you choose to anchor up, by the way, doesn’t mean that you have to keep your bait or lure sitting in one place all day. In fact, you’ll probably be more successful if you don’t. If you’re fishing bait, rather than using a sinker heavy enough to hold it in place, go a little lighter and try a lift-and-drop technique while paying out a little line at a time, allowing your gear to bounce back and cover some ground as it rolls away from the boat, similar to how you might do it if you were back-bouncing for river salmon or steelhead. If you use leadheads or metal jigs, you can accomplish the same thing by lightening up on lure weight and yo-yoing it back 100 feet or so before reeling in and starting over.

Another strategy is to reel in 15, 20, maybe 30 feet of line every few minutes, hold your bait or lure there for a few seconds, then free-spool it back to the bottom. Getting your gear up into the water column like that makes it visible over a larger area and, if you’re using bait or scent, helps to spread the smell over a larger area, potentially catching the attention of any sensitive halibut nostrils in the vicinity.

I mentioned earlier that you might need to pay out a lot of anchor line to hold your boat, depending on the style anchor you’re using, size of your boat, depth you’re trying to fish and water conditions. There aren’t any hard-and-fast rules about how much “scope” you’re going to need out there, but you could easily encounter situations where you need to multiply the depth by two, three or more times to have enough line to hold safely and effectively.

The release type anchor systems such as those used on the Columbia, by the way, are also becoming popular on the Northwest halibut grounds. They take a lot of the sweat and tears out of anchor retrieval and are especially handy should you hook a barn-door fish and have to give chase. If you’re not familiar with these anchors, do a little research before your next halibut trip.

As it is when fishing off the anchor, an important factor in drifting success is to fish the right spots; edges, gentle drop-offs, nears the tops of humps and plateaus, current breaks and, when you can locate them, places where baitfish are congregated.

Although they will certainly seek out and follow bait—both along the bottom and up and down through the water column—halibut are primarily ambush feeders, often waiting at the shoulder of a break-line or similar hiding spot and pounce on any potential food source that swims by or is washed past in the current. The key to drifting is to keep moving, always bouncing your bait or lure along new real estate in hopes of drifting it past a waiting halibut. You don’t necessarily have to move fast, but you don’t want to sit in one spot for half an hour at a time, either, especially if that spot is flat and offers nothing in the way of halibut ambush cover.

Drifting “downhill” is usually most productive, because it lets you bounce your offering over the shelves and edges where fish wait, while reducing hang-ups and lost tackle. A typical strategy is to start near the top of a hump or drop-off, pay out line to stay near bottom as you work your way down the slope, then, as the bottom flattens out (or you reach a depth that you no longer feel you’re fishing effectively), you bring up your gear and run back up-slope to start a new drift.

That’s not to say you have to fish downhill all the time. “Bumpy” ocean bottoms with no significant overall depth change may offer lots of little humps and drops where bait congregates and where halibut can find good hunting. And, when conditions are right, you may be able to fish while drifting uphill. This is best accomplished around a slack tide, when you can fish a vertical line angle to reduce hang-ups. Even then, though, you’ll have to stay on your toes and continually retrieve line to stay in touch with the bottom, avoid losing gear, and maintain a tight enough line to detect and react to strikes.

It should go without saying that you have to keep your bait or lure close to the bottom while drifting for halibut, but don’t drag bottom. Dragging hooks and sinkers along the ocean floor is a sure way to waste not only money, but fishing time, even over the generally forgiving cobble, gravel and sand bottoms that halibut tend to prefer.

As suggested earlier to anglers who anchor, those who drift for halibut should make it a practice to work their baits and lures up and down through the lower 20 or 30 feet of the water column as they fish. Bouncing bottom with your jig or your sinker sends an audible signal through the water that halibut may use to home in on your gear and also makes your offering visible over a larger area. Reeling your rig several yards up into the water column once every few minutes also increases its visibility and helps to spread scent from your bait over a larger area, all of which increases the chance that a hungry Halibut may find it.