Hook to Cook

Nutritionists, doctors, and other health experts all agree that seafood can form an integral part of any balanced diet. Fresh fish in particular is both delicious to eat and highly beneficial to our well-being. In addition to a broad range of essential vitamins and minerals, many fish also contain high levels of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids – substances that boost the human metabolism and that have been linked to a variety of positive health outcomes.

Recreational anglers enjoy the unique opportunity of catching, preparing, and cooking their own fish, potentially saving money and also benefiting from access to much fresher seafood than is typically available from a market, fish monger, or restaurant. Eating select fish you have caught yourself on a small scale, recreationally, is also arguably more sustainable than any other form of seafood consumption. However, to optimize this self-caught seafood experience and diminish the risks of food poisoning, and other problems, it’s essential that anglers know how best to handle their catch between water and plate.

Know Your Catch

To begin with, never consume self-caught seafood unless you’re absolutely sure of its identity! Certain species (particularly members of the pufferfish clan) have deadly poisons in their internal organs, while others may carry location-specific threats such as ciguatera, a toxin occasionally found in fish (particularly those from tropical and subtropical waters) known to have consumed dangerous microorganisms known as dinoflagellates, which live on certain algaes and corals. If fishing new waters in tropical regions, always talk to local residents about the likelihood of encountering this problem, and discuss which species to avoid eating.

It may also be unwise to consume fish from highly polluted waterways or to regularly eat the flesh of larger, long-lived marine predators, including swordfish, sharks, and tuna, that can potentially bio-accumulate heavy metals such as mercury in their muscle tissue. Most countries, states, and territories publish up-to-date advisories related to safe fish and shellfish consumption. Take the time to search out these advisory notices and familiarize yourself with their content.

Humane Dispatch

Any living creature intended for human consumption should be killed in the most humane manner possible. Leaving a fish to flap around and slowly expire from suffocation is not only cruel and unethical, but can also cause serious degradation of the flesh, diminishing its value as food. This process begins even before the fish is landed. Minimize the time a fish fights against the hook and line: extended encounters can cause a build-up of lactic acid and other stress-related chemicals in the fish’s flesh, causing it to deteriorate. Land your fish as quickly as practical, and either carefully unhook it and return it to the water, or kill it immediately if it’s intended for the table.

There are three major methods used to dispatch fish: (a) a sharp blow to the head, (b) severing the spinal cord, or (c) a Japanese technique of brain spiking known as iki jime.

Blow to the head: Striking a fish firmly on the top of the head with a wooden or metal club is a well-established method for subduing and killing the catch, and is especially popular when dealing with large, powerful, and potentially dangerous marine species such as sharks, tuna, mackerel, halibut, and the like. When dealing with some of these fish, several blows may be necessary to complete the job.

As an interesting aside, a small wooden club traditionally carried by trout and salmon fishers for performing this task was often referred to as a “priest,” because it was used to administer the “last rites”!

Severing the spinal cord: Cutting through the area known as the “throat latch,” under and between a fish’s gills, before bending the creature’s head back sharply to break its spine and sever the spinal cord, not only kills the catch quickly, but also allows it to thoroughly bleed out. Bleeding can be an important step in optimizing the food value of many species, especially blood-rich fish such as tuna and mackerel. However, while this method is certainly effective, especially with smaller fish, it can also be extremely messy and rather unpleasant to perform.

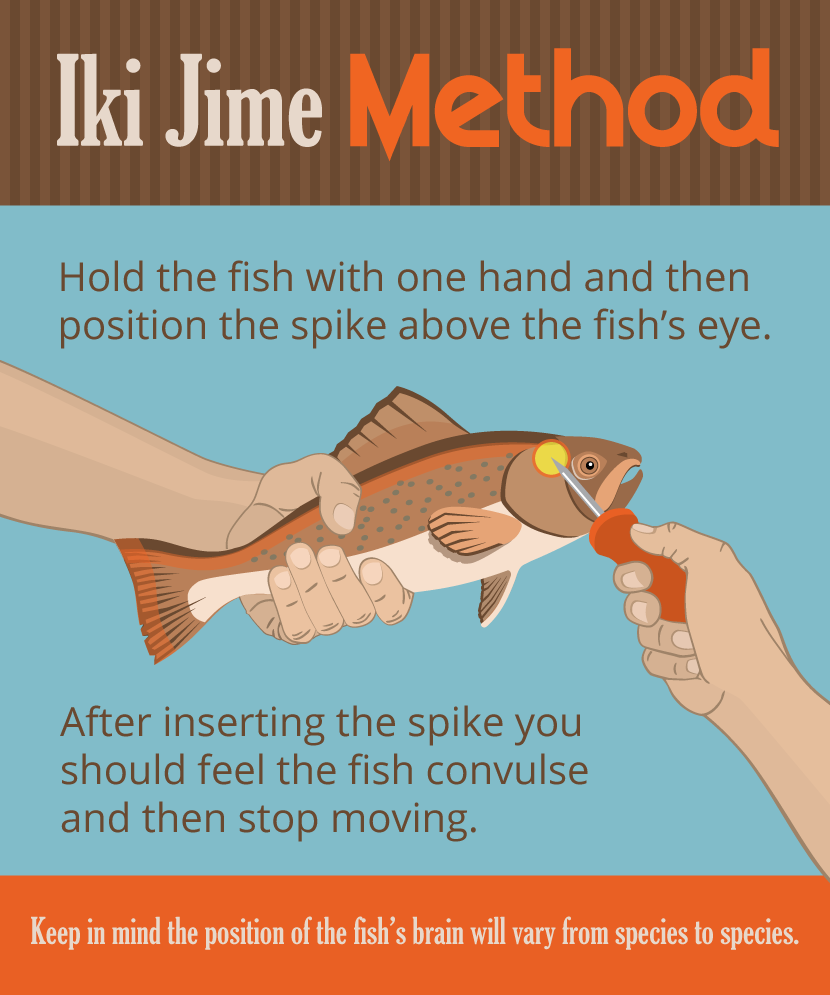

Iki jime brain spiking: Favored for centuries by Japanese fishers, the use of a sharp, metal spike to quickly pierce and destroy the brain of a fish is arguably the most effective and humane way of all to kill any catch. However, performing this task efficiently involves having a reasonably good idea of the fish’s physiology and being able to accurately locate its relatively small brain. The precise location varies between species and families of fish.

Keeping Your Cool

From the moment a fish is killed (ideally using one or more of the techniques just described), bacteria already living in its gut cavity, bloodstream, and flesh will begin to multiply. Other bacteria may also be introduced into the carcass via external wounds such as iki jime spike holes or incisions made to bleed the catch. Reducing the temperature of the fish can dramatically slow the growth of these potentially harmful bacteria. This is less of an issue in cold climates but can be absolutely critical in warmer parts of the world if spoilage is to be prevented.

For air and water temperatures below about 65° Fahrenheit (18° Celsius), it may be sufficient to simply place the catch in a shaded location and cover it with a damp towel or cloth, especially if it will only be stored this way for an hour or two before further processing and refrigeration. However, in warmer conditions, it’s very important to quickly pull the temperature of the carcass down and hold it as low as possible (ideally just above freezing point) until the catch can be cleaned and butchered. By far the best way to do this is to completely immerse the fish in an “ice slurry” consisting of crushed or cubed ice and salted water (clean seawater, if you’re fishing in the ocean). Fish placed in such an ice slurry retain their color, firmness, clear eyes, and flesh quality for many hours or even days, and are much easier to handle and process later.

You Caught ’Em, You Clean ’Em!

Very few people would rate cleaning the catch as one of their favorite parts of the fishing process, but it’s nonetheless a crucial job if we wish to enjoy the fruits of our efforts in the form of delicious and healthy meals of self-caught seafood. My best advice is not to put it off for too long after landing your catch: roll your sleeves up and get stuck into it!

There are three main ways of cleaning and preparing fish for storage in the freezer or refrigerator and, ultimately, cooking and serving them. Those methods are: (a) gutting, gilling, and scaling; (b) filleting; and (c) cutleting or steaking.

Gutting, gilling, and scaling: This is the most common way of cleaning the catch and may be used both as an end in itself (when planning to cook a fish whole) or as a first step prior to one of the other preparation methods described here.

To gut most fish, insert a sharp knife into the vent and slice all the way forward to the gills. Be careful not to insert the knife too deeply, as it’s best to avoiding splitting open the stomach or other organs and spilling their contents. Once the gut cavity is completely opened, carefully remove all of the entrails and also the entire gill assembly. You may need to cut around the bases of the gill arches to facilitate their removal. Most fish also have a blood-filled sack concealed behind a membrane running along the top of the gut cavity, directly under the backbone. This is actually the fish’s kidney. It’s best to remove this organ completely using an old teaspoon or a stiff-bristled brush before thoroughly washing, draining, and drying the empty stomach cavity.

Fish may be scaled either before or after gutting, using a specially designed scaler or the back of a knife blade to lift the scales away by stroking briskly forward, from the fish’s tail towards its head (don’t use the knife’s cutting edge, or it will quickly be dulled).

Filleting: This is an extremely popular method for butchering most fish and may be performed on an intact carcass prior to gutting, gilling, and scaling, or after that first step has been performed. (If the skin is to be left on the fillets for cooking, the fish should be scaled before filleting.)

Fillets are best removed by carefully cutting down to the backbone just behind the fish’s head and gills before laying the knife on its side and cutting towards the tail, keeping the blade as close as possible to the bone structure to minimize wastage. It should also be noted that some people prefer to fillet from tail to head. Fillets may be skinned after removal, if so desired, and additional lines of smaller bones can be trimmed away or even removed with tweezers or forceps.

Cutleting or steaking: Some large fish are prepared for cooking by slicing or sawing straight down into the fish and through the backbone at 90 degrees to produce steaks or cutlets. This may be done with a stiff knife (standard or serrated) or hand saw, or even with a commercial butchers’ band saw. If using a band saw, it’s often easier to freeze the catch first. Because the skin is typically left on steaks or cutlets, most fish should be scaled prior to this operation.

Storing Fish

Once cleaned or butchered, fresh fish may be held in the refrigerator or on ice (ideally covered in cling wrap film or aluminum foil) for up to five or six days without significant deterioration, so long as their temperature is maintained at below 40° Fahrenheit (5° Celsius) and any liquid is immediately drained away from the fish.

For longer-term storage, completely seal and then freeze the fish rapidly while fresh and hold it at a temperature of no more than 5° Fahrenheit (-15° Celsius). Vacuum sealing fillets or portions in plastic sleeves before freezing prevents freezer burn and greatly extends their frozen shelf life.

How long frozen fish will keep without significant deterioration very much depends upon the fat or oil content of the flesh. Leaner fish can be kept longer, but as a rule, all frozen fish should be thawed, promptly cooked, and eaten within three or four months of capture, and should never be refrozen after thawing.

Look after the fish you catch, treat them as the valuable resource they represent, and enjoy one of the greatest bonuses of the recreational angling process: putting fresh seafood on the table for you and your family and friends to savor. Bon appétit!